Back in 2012, Americans became familiar with Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) after a short documentary film produced by Invisible Children promoting the “Stop Kony” movement went viral. The Ugandan cult and militia leader was reportedly responsible for war crimes, the forced recruitment of child soldiers, the abductions of young girls, and terrorist activities in Uganda.

Among the worldwide response was the deployment of American Special Forces soldiers by then-President Barack Obama. Their mission was to advise and assist Ugandan security forces in killing or capturing Joseph Kony and eliminating the LRA. Troops from the United Nations and several African countries joined the effort and today, while Joseph Kony remains at-large, the LRA’s capabilities are greatly reduced. In 2012, their numbers were somewhere around 3,000 strong. It is believed that only 100 soldiers remain in the LRA, and the United States and Uganda have called off the hunt for Kony, no longer considered a threat to Ugandan security.

How was the effort against Kony and the LRA so effective with so little American presence and no direct combat? The answer is the successful employment of U.S. Army psychological operations, or PSYOP, teams. Attached to Special Forces teams, PSYOP soldiers are a part of United States Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) and specialize in military information support operations (MISO). These are operations conducted through the dissemination of messages aimed at influencing a target audience’s behavior. The dissemination in this case was done through radio broadcasts, loudspeaker messages, and leaflets. The target audience was the soldiers of the LRA.

Psychological warfare is nearly as old as warfare itself. Since prehistoric times, armies have used various methods of psychological warfare to instill terror in their enemies to achieve one goal: intimidate the enemy and influence them to give up. It has been used with varying degrees of success but has remained constant through the history of warfare.

Psychological operations conducted today by the U.S. Army are vastly more complex than simply intimidating the enemy. While leaflet drops on Iraqi troops in Operation Desert Storm were influential in convincing many of these troops to surrender to coalition forces without firing a shot, PSYOP teams operating in Iraq and Afghanistan after 9/11 have performed missions with a focus on not just the enemy but also the local civilian populace.

In Uganda, the mission was straightforward: disintegrate the LRA by persuading its leaders and soldiers to defect.

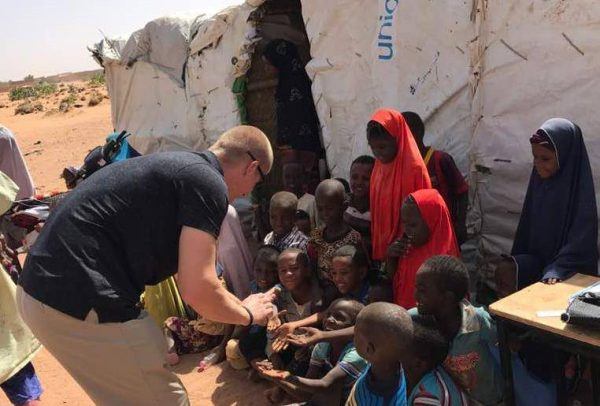

Army Colonel Bethany C. Aragon is the commander of the 4th Psychological Operations Group (Airborne) at Fort Bragg, one of two active duty psychological operations groups in the Army (the rest are a part of the Army Reserve). While speaking at a conference in Washington, D.C. this past fall, Colonel Aragon described how the PSYOP team attached to a Special Forces team deployed to Uganda and used leaflets, radio messages, and loudspeaker broadcasts to encourage LRA soldiers to defect.

“In the beginning, we had broad target audiences. Knowing that most of the LRA combatants were child soldiers who had been abducted, we assessed that they were susceptible to defection. It was a significantly dense jungle. The best means to access our target audience was through radio, leaflets, aerial loudspeaker operations,” said Colonel Aragon.

As part of any PSYOP campaign to influence enemy soldiers to change their behavior, an incentive needs to be provided. In this case, the Ugandan government offered amnesty to LRA soldiers who put down their weapons and defected.

The defections created a perfect cycle for the U.S. Army PSYOP team. Soldiers would defect from the LRA and provide priceless intelligence to U.S. and Ugandan forces that helped them improve the targeting-and-influence campaign, leading to even more defections. The PSYOP teams would use the intelligence to create even better products aimed at influencing higher levels of the chain of command in the LRA to defect. This ultimately led to the defection of Michael Omono, Joseph Kony’s personal radio telephone operator and a man with valuable information on Kony’s communications.

The special operations forces concluded the operation in the summer of 2017, as the number of fighters in the LRA fell to below 100 and the group was no longer considered relevant to the security situation in Uganda.

The successful operation against Kony and the LRA places psychological operations in the spotlight and may force commanders to reevaluate future operations. The growing influence of the Internet and social media means that information operations and psychological warfare will have a greater role in future conflicts.

In recent years, the Islamic State of the Levant (ISIL) took advantage of the power of the information environment, particularly the Internet and social media, for propaganda purposes. The impact this had was profound. Scores of young men and women were recruited worldwide, influenced by the Islamic State’s persuasion methods. The group also created an image of themselves as ruthless and powerful, which instilled fear in many adversaries.

U.S. and partner nation forces, operating primarily in Iraq and Syria, conducted PSYOP campaigns in response against the Islamic State. Leaflets dropped over Raqqa, the Islamic State’s “capital” city, depicted ISIL as a death machine with young men joining the group…being led directly to the grinder. Other leaflets, intended for the civilian population, were dropped over cities like Mosul and urged the local population to stand up to the Islamic State and collaborate with Iraqi security forces. The coalition even utilized social media accounts on Twitter to distribute similar cartoons.

While the effectiveness of psychological operations against the Islamic State has been debated, it is becoming clear that there will be an opportunity to employ more PSYOP in our ever-shrinking world. The advancement of global communications has created an environment where information operations and propaganda will have a greater role in influencing enemy forces and civilian populations in hostile nations.