The previous article in this series started with Ji Seong-ho’s telling of the privations suffered by his family, in spite of his father’s position as a Party member. It covered his injury while foraging for coal to trade for food, and the amputations without anesthesia. Ji recounted his first trip into China to look for food, and the beatings and torture he received from North Korean authorities upon returning from China.

After that experience, Ji resolved to leave North Korea, and convinced his family to do the same. “I realised that this was a land I never wanted to stay in. I wanted to move to a land where I could be treated as a human, whether that was South Korea or somewhere else. That’s why I defected in 2006.”

Crossing Into China

The Ji family started their escape with Seong-ho and his brother crossing into China. They swam across the river Tumen, where he almost drowned because of the difficulty managing with his amputated foot and hand. The brothers were surprised that there was no South Korean embassy in every Chinese city. When he realized he would have to find his own way to a free country, he almost gave up and went back.

“Once my brother and I were in China, I decided we should go our separate ways. If we were arrested, we would both be killed.”

The family had devised a strategy to have members go in separate groups. They reasoned that if any family members arrived safely, they could help the others who were still on their way. Ji Seong-ho spoke with archivists from the Freedom Collection, where a transcript of his interview is available.

“Once my brother and I were in China, I decided we should go our separate ways. If we were arrested, we would both be killed. At least my brother could succeed in the journey to South Korea and bring my father there. Then he could find my mother and sister. So there in China, I said goodbye to my brother. He and I would go separately. He departed for Thailand. I left 15 days later.”

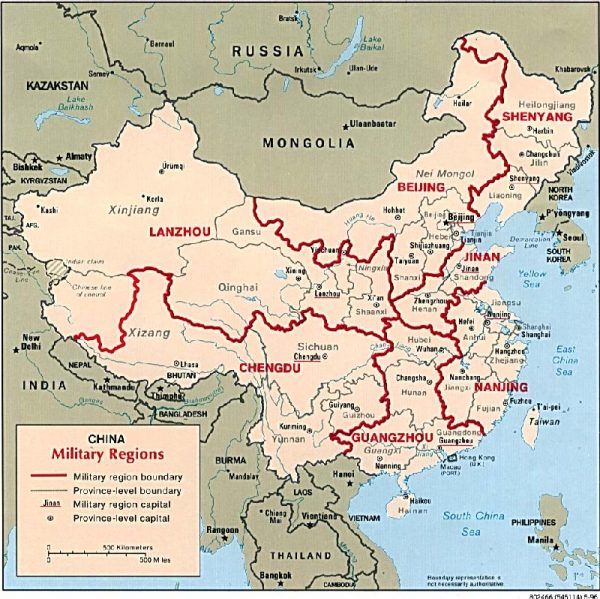

The enormity of the task ahead dawned on Seong-ho again, when he set out after his waiting period. “During that journey I realized how big a country China was. I moved in secret from one place to another, and fled at the sight of the police. It was quite a challenge. I think it took almost one month crossing the Chinese countryside before I could enter into a Southeast Asian country. Sometimes I had to walk, and sometimes I managed other modes of transportation.”

Finding God On the Mountain

Ji faced two major difficulties. First, he was handicapped by his injuries. He used his home-made wooden crutches to get around, so he moved slowly, looked vulnerable to any unscrupulous observers, and was easy to identify and remember.

“If there is a God in this world, please save me. If you do, I will go to South Korea and lead the best life that I can.”

Second, he had no passport and no entry visa. Had he been found by the police, he would have been arrested and returned to North Korea. He knew what that would mean, having already faced torture just for having visited and returned by his own choice.

Ji said the most difficult part was crossing into Laos, because he had to climb a mountain with is crutches. He felt despair, and again nearly gave up. “At one point, I thought I might actually die there in the jungle, because I had no strength left to carry on. I remember asking myself, ‘Why am I here? What happened to North Korea and what happened with inter-Korean relations that situations have come this far?’”

It was during this mountain climb that he began to think of God. “I remember praying to the heavens saying, ‘If there is a God in this world, please save me. If you do, I will go to South Korea and lead the best life that I can.’ Perhaps my prayers were answered because fortunately, I made it to Thailand, safely with other people.”

NAUH and ‘Small Unifications’

From Thailand it was relatively simple to make it to South Korea, where Ji has made good on his promise to God. He founded an organization called NAUH, which is dedicated to fostering cultural exchanges between young adults from both North and South Korea. NAUH also broadcasts radio messages into North Korea, and helps North Korean refugees integrate in the South.

Seong-ho calls this process a ‘small unification.’ “A small unification refers not to unification in its political or economic context, but rather, refers to a personal, person-to-person level. It entails becoming friends with North Korean defectors living in South Korea and learning to coexist and dream together with them.”

Ji Seong-ho’s greatest regret is that he was unable to help his father. His father was caught trying to escape North Korea. “To this day, I am emotionally burdened over the fact that I wasn’t able to keep the promise that I made with my father. I was supposed to go back to get him and bring him either to South Korea or another country to lead a better life but because he was arrested in the process of escaping and was tortured, he died. I still have a hard time forgiving myself for that.”