Member states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) met recently at a summit in the northern China port city Qingdao. The timing of the conference could not have been more apropos. The SCO summit opened just as the G7 conference in Canada was coming to an end. The SCO bloc is in many ways the counter-force to the West’s economic and military cooperation. As tensions build between America and Europe on the one side and China and Russia on the other, initiatives of this organization are now more important than ever.

What Went Down

The actual focus of the summit was geared toward trade barriers as emerging epidemic threats. The communique on trade stated the group’s “intent of simplifying trade procedures between the countries.” Member states hit a number of points including “decreasing the number of customs formalities on imports, exports and transit of goods, increasing transparency, developing cooperation between border agencies, including customs, and expediting the transit of goods.”

On the issue of disease prevention, leaders highlighted the growing danger of epidemics in the SCO space due to “increased cross-border movement of people and trade liberalization.” Sicknesses that have been on the minds of state leaders include “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHF), cholera and other particularly dangerous infectious diseases.” A joint statement emphasized the “resulting need to enhance the sanitary and epidemiological safety and the protection of public health.” To this end, nations committed to “improvement of national laboratories, the development of research centers and joint research projects” on public health.

The conference could of course not go without leaders flaunting their achievements and lambasting their global adversaries.

As the summit was just beginning to get rolling on 10 June, Chinese President Xi Jinping welcomed the newest participants in the SCO, Pakistan and India, calling their presence “of great historic significance.” Islamabad and New Delhi both came into the SCO last year in early June. “More member states means greater strength of the organization as well as greater attention and expectations of people of regional countries and the international community,” Xi said.

SCO nations praised the “unity” of the event, which got under way just as the Group of Seven summit in Canada was ending in what appeared to be disarray. The G7 meeting was marked by President Trump’s notorious hardline stance on trade. The final communique produced by the leaders of the US, Canada, Britain, France, Italy, Germany and Japan agreed on the need for “free, fair and mutually beneficial trade,” and the importance of fighting protectionism. “We strive to reduce tariff barriers, non-tariff barriers and subsidies,” the statement said. But only hours after the meeting ended, Trump had disavowed the communique, essentially withdrawing America’s commitment to any of the listed goals.

In a thinly-veiled criticism of the United States, Xi stated at an opening ceremony that the SCO states “reject selfish, shortsighted, closed, narrow policies. [We] uphold World Trade Organization rules, support a multilateral trade system, and building an open world economy.” The Chinese leader avoided mentioning the US or Trump by name.

What is the SCO and Why is it Important?

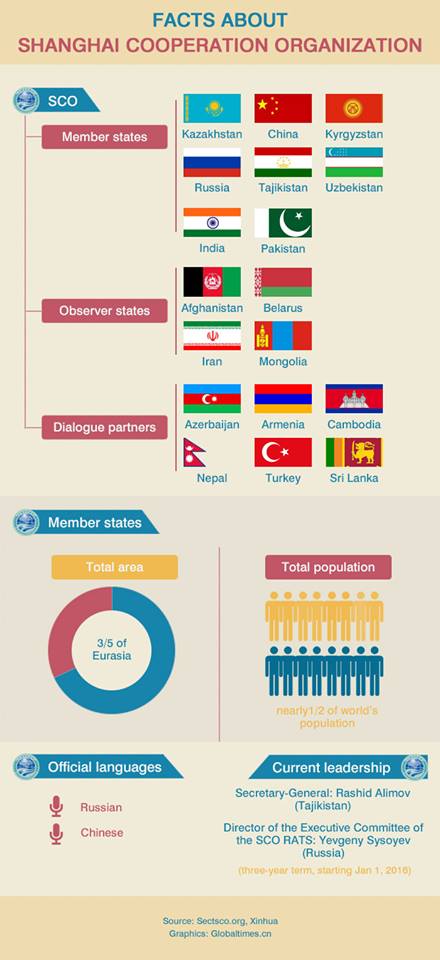

The SCO as it exists today started off in 1996 as the Shanghai Five (for an attempt to copy the Group of Seven model, one would have thought they could come up with a more original name). In 2001, the current SCO was launched with founding members of China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. After the additions of India and Pakistan in 2017, SCO became the largest regional organization in the world in terms of geographical coverage and population, covering three-fifths of the Eurasian continent and nearly half of the human population. Although their economic influence doesn’t quite match their sheer size—all the member states combined make up a quarter of the world’s GDP—the group does represent a powerful force in the global market. From this perspective of pure size, the SCO is one of the world’s most powerful and influential organizations.

The Global Times, a Communist Party newspaper, said in a commentary on June 10 that unlike Western organizations like NATO and the G7—which seek to “consolidate the global economic order that is favorable to the Western world”—the SCO is inclusive. The group “is an organization of equal cooperation aiming to resolve security issues that concern its member states, instead of serving the interests of certain dominant powers. It is not a tool for geopolitical games, seeking hegemony or engaging in international confrontation. Its only goal is to solve problems through collaboration and common development”

SCO’s spirit of “inclusivity and cooperation” lauded by the Chinese should not be taken cynically by Western critics. The cooperation the group has successfully pulled off between member states is pretty impressive. While some members are natural allies, the SCO umbrella has pulled together countries that have very serious grievances against each other. Take the issue of Tibet and its unofficial political leader, the 14th Dalai Lama. India has been offering protection to the chief Buddhist monk ever since China conquered Tibet in the late 1950s. To China, Tibet is an extremely sensitive core issue. The Chinese find it unacceptable when they see the Dalai Lama treated as a VIP, or even akin to a head of state, because they view it as a challenge to China’s national sovereignty and claim over Tibet.

Relatively minor interactions between the Dalai Lama and heads of state have turned into major international incidents. For months, China gave Germany the cold shoulder after German Chancellor Angela Merkel met the Tibetan leader some five years ago. After French President Nicolas Sarkozy met the Dalai Lama in 2008, China cancelled a high-profile summit with the EU in response. Even President Obama kept his meetings with the Dalai Lama in the White House residence, instead of the Oval Office where the President normally meets world leaders.

This point of tension between China and India is in addition to issues of huge trade imbalances and regular military incursions that have erupted into three separate wars over the years. As well, Pakistan and India have a long history of conflict going back to the two countries’ independence some 70 years ago. Border conflicts and skirmishes are the norm, especially in the heavily contested Kashmir region. Earlier this year, an attack on an Indian army base in Jammu, allegedly emanating from Islamic militants based in Pakistan, demonstrated how the years-old conflict between the countries still wages on, nearly a year after the two nations agreed to join the same international group. Indeed, European observers have commented that even the original SCO with its core membership contained a wide spectrum of interests, often conflicting. Despite this, the group is able to stay together and function with some level of cohesion.

The question of course is: Will the SCO—especially now with its amplified membership—eventually form a significant threat to US interests?

The answer is maybe.

The is no doubt the SCO has some anti-Western and anti-American undertones. SCO summits have been used in the past as platforms for uniting against American interests and attacking policy decisions, the most recent instance being Xi’s speech, implicitly attacking the US on free trade. Attempts by the US in the past to be involved in SCO activities were summarily rebuffed. Back in 2005, the SCO issued a demand that the US remove its military bases in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, which Washington eventually did.

So yes, the SCO can give a platform to anti-American initiatives and can make things difficult for the US in Central Asia. But the emergence of a powerful bloc to deeply affect US global interests has not happened yet. Nor is there any indication that the member states have the wherewithal to do this, either economically or militarily. In fact, as many observers have pointed out, SCO’s main success is likely the cohesion and decreased hostility it creates between its own members. This is something the US wants anyway. After all, war is bad for business.

The one real concern for the long term is that SCO could give a political “home” for countries that have been alienated by the West in general or the US in particular. One could make the argument that this has been occurring slowly with Pakistan, a nation that has been a troublesome ally of the US for years. Nations that feel rejected by the US and its Western partners could be very tempted by the SCO and its inclusive ethos.

While far from an existential threat, American policymakers will no doubt keep a more watchful eye on the growing SCO as its members seek to consolidate the growing power of Eastern nations.