Writing a recently published piece regarding a Massachusetts bill seeking to legalize EMTs treating police dogs injured in the line of duty reminded me of a particular call I received as a rookie policeman. I was fresh out of the police academy and paired with a field training officer (FTO). The call came in as a relatively routine one in Florida: an alligator under someone’s car parked in their driveway. I recall that the frantic homeowner was doubly frightened because she was just about to take her children out in said car. Luckily, she made a trip to load child-rearing supplies first, enabling the opportunity to see a dark-green prehistoric-looking tail accompanied by whiffs of a strange odor. (Gators absolutely stink!)

Police trainer and I arrive and see the mom standing around the corner, close to her front door, many yards away from her driveway, peering around as if the thing had a bazooka trained on her. As a nature buff, I was excited to be in charge of this wildlife encounter. But that soon changed to confusion and frustration.

We radio’d to police dispatch that we could see the large gator, pretty much parallel to the woman’s car…just chillin. Then it got really interesting. My FTO informed dispatchers that we were going to try and coax the gator out with a dog pole (a lengthy lightweight pole with a noose on the end, ordinarily used to catch stray dogs) and steer it back to a nearby body of water (definitely common in Florida).

That was the objective until the testiness evolved and we were essentially sidelined to gator-sitting duty.

Indeed, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC) has a lengthy list of Alligator Regulations and Associated Statutes, one of which at one time prohibited me and my trainer, duly-sworn law enforcement officers, from touching the stinky beast in any way for any reason. The expression on the mom’s face when we informed her we were not to touch the gator and that state cops were coming for it was…one of dismay. Her snarky verbal response also telegraphed discontent: “How long is that gonna take?” We understood beyond her question. Two local cops standing by on-scene until state cops arrived was a twist that never came up in law classes at the academy. Of all the proverbial what-ifs asked in police studies, this one was not even on the mind…until the state made a bigger stink than the gator.

The concerned mom turned the corner of her mouth, as if to non-verbally express I don’t get it. Neither did we. She dropped her head and went back inside. My head lowered too; it was an embarrassing stalemate.

Ornery Part

Turns out that particular state statute did exist and spelled out all protections, in favor of the alligator. A portion of the law declared that no law enforcement officer other than trained sworn state wildlife officers can physically handle, appropriately bind, and ultimately relocate any alligator from public premises or places of private inhabitancy. Who knew! I got the feeling the reasoning behind this matter was betrayed by the word “trained,” which, in retrospect, made sense since no police academy ever hinted at How to arrest an alligator principles.

As I recall, the folks at FWC taking the call from our dispatchers made some rather ornery-laden statements…to the tune of “arresting” anyone who touches the gator. We were both on duty, in complete police uniform, and in control of a wild animal under a parked car in our jurisdiction. Surely, we were not about to let someone walk up and try to molest the large, deadly lizard. How else were we to perceive the FWC message? “Oooh, us too!” I’ll keep the language to G-rated. And that “G” does not stand for government dudes pissed at other government dudes; that would be more like R-rated stuff.

What did me and my FTO do?

Well, my trainer was widely known for his stellar knowledge of state laws, to the point of arrogance. This scenario was difficult for him to swallow. So he made a few calls to argue his case (he had that penchant when he felt blindsided or made to feel behind-the-eight-ball) and learned directly from the deputy police chief that, in fact, such a law was on the books, to include threat of arrest (no matter who was in violation and his/her authority). Yikes! That’s one way to learn a statute and never forget it.

Politics in Policing

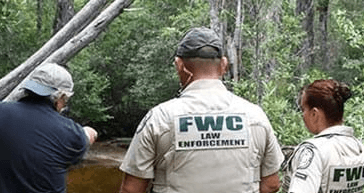

You can say this scenario set the tone of tension between agencies. When the FWC officer arrived, he was less chatty and more focused, seriously sizing up the situation. There’s roughly 800 FWC cops statewide. Of the portion on duty at any given time, they are tooling from call-to-call and, by default, restrict their time on scenes. Understandable. My FTO threw some barbs but the wildlife cop didn’t necessarily bite. He simply paraphrased the “gator law” and geared up to take-hostage the gator and “return it to the wild.” (Ordinarily, state conservation cops drive such beasts as far away from residential areas as possible, at which point they release the critters into habitats without mailboxes.)

Not animal-related but similar in police political context is something which transpires in my neck of the woods. In a neighboring county, the sheriff’s office policy is for the state troopers to work (investigate) all traffic crashes on state roadways and federal highways. If a county deputy rolls upon an unreported crash, the deputy’s dispatchers notify the Florida Highway Patrol to respond. In the name of jurisdiction or staffing levels or whatever, that is how some agencies choose to operate. What that also does is make all parties involved in the crash more mad, thus frowning upon the law enforcement profession. A duly-qualified county cop informing crash victims that they’d have to wait even longer, until another duly-qualified cop came to investigate an already stressful experience…does nothing for public relations service to the public. Citizens want service, not logistical deficiencies or philosophical dismissiveness.

My department assumed responsibility for everything in its jurisdiction; although it equated to tons more to do, it fulfilled the mission (promise) to readily and competently serve victims without additional undue inconvenience to them.

I gather this is how the mom with an alligator in her driveway sized up the state of affairs, being told by two cops that she’d have to wait for other cops to arrive.

The entire ordeal was humbling. It was also thought-provoking, compelling me to wonder what other obscurities were embedded in laws I should probably know to-the-letter.

And it would happen again when I was a FTO myself with a trainee in my cruiser. We receive a request to back up another officer who joined our agency after formerly serving as a wildlife officer with the FWC (irony). He had located several “suspicious” folks down by the river, at dusk, and checked out with them. He was solo and in contact with a group of five males. My trainee and I arrived; our flashlights located Officer S. at the river’s edge, sighting down from a steep street-level incline. That type of terrain poses an officer-safety risk. Side-stepping it down to his position, we landed on mucky land. Once closer, I saw bamboo poles. Another officer-safety threat. Naturally, each pole had a hook; more officer-safety concerns.

In short, at their feet were three clear-plastic bags of water containing pet store-bought goldfish. A former Marine drill instructor, the lead officer was stern. I admit I was amused. My trainee squinted his way through it too. What the…?

Turns out the former-FWC-officer-turned-city-cop knew of a state statute delineating a misdemeanor violation for using goldfish as fish bait (he witnessed them bait and dunk before he made contact), thus providing the probable cause to detain and investigate. That lawful scenario pillared by another obscure but valid law netted him three arrests for outstanding warrants. In the rear seats of patrol cars they went, in the bag remained live evidence, and on digital film was imagery of the shiny orange fishes (in the event of court presentation). Again, a humbling police encounter which became an indelible feat which I used with all police trainees I had thereafter.

Then and Now

Whereas the law leading to the gator impasse described above may seem ludicrous (cops who want nothing to do with gators may opine differently), the state’s FWC has since walked back the ritual, to the point of subcontracting civilians known as nuisance alligator trappers. Nowadays, whenever alligators are reportedly encroaching too close to humanity, the FWC has the following PSA pitch: “If you believe a specific alligator poses a threat to people, pets or property, call our toll-free Nuisance Alligator Hotline at 866-FWC-GATOR (866-392-4286), and we will dispatch one of our contracted nuisance alligator trappers to resolve the situation.”

Among my wildlife-oriented police career, I’m so glad I played a role in saving several bags of goldfish from the clutches of bass and other hangry river-living things.

Incidentally, I harbored no grudges with my brother/sister LEOs with the FWC; the law is the law. Like other statutes which may have wrinkled my brow, whether or not I agree with legal premises is always second to oath fulfillment and law enforcement.